by Crystal R. Sanders

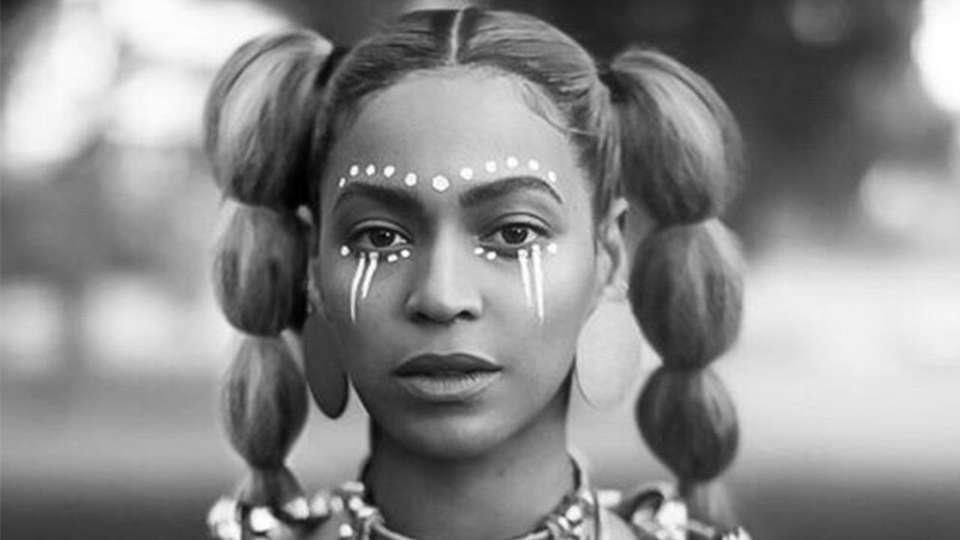

Singer, songwriter, and actress Beyoncé Knowles Carter broke Twitter and every other social media outlet with the release of her visual album Lemonade that explored the hopes, dreams, pain, and joy of black women. At the end of one song on the album, Jay-Z’s grandmother is heard saying, “I was served lemons, but I made lemonade.” Making lemonade has been a revolutionary act and a survival mechanism for African American women throughout history. Bearing the dual burdens of racism and sexism, black women have not only played the hand dealt, but have come up trumps. In essence, they made the sweetest, coldest lemonade possible.

As a scholar of African American history who has published a book about black women and taught courses on black women’s history, I cannot let this Lemonade moment pass without setting the record straight. Black women have made lemonade for centuries. One is only privy to the lemonade when the stories and experiences of black women and girls are moved from the margins to the center. Indeed all of the women are not white and all of the blacks are not men.

Scholarship about black women’s lemonade stands abounds. The literature shows that during slavery, when denied the benefits of womanhood, or worse, humanity, bondwomen fought back in a variety of ways. Whether it was feigning illness on the day of an important event in the Big House or decorating one’s slave cabin with newspapers though barred from learning to read and write, black women found ways to address their hurt and assert their presence. In 1895, after a white journalist characterized all black women as prostitutes, black women from various parts of the country began collecting their lemons and sugar. Rather than retreat out of shame, black women mobilized and created the National Association of Colored Women (NACW) in 1896. The NACW’s brand of lemonade included kindergartens for black children and voter registration drives for black adults. When W.E.B. Du Bois and Oswald Villard purposefully left Ida B. Wells-Barnett’s name off the list of the NAACP’s founders, Wells-Barnett took her activist talents to local black organizations that understood and valued the contributions of black women. After an assassin’s bullet killed her husband, Coretta Scott King made lemonade. She purposed that the same federal government that surveilled her husband would honor his life and legacy with a national holiday.

Beyoncé’s album is a mere peek into a long history of black women’s production of lemonade to heal and free themselves from all forms of physical, mental, and emotional degradation. Stories of love, redemption, forgiveness, mobilization, and agitation can be found in the lemonade. Below is a list of history books that explore black women’s lemonade in slavery and in freedom. This list is in no way exhaustive.

Stephanie M.H. Camp, Closer to Freedom: Enslaved Woman and Everyday Resistance in the Plantation South

Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham, Righteous Discontent: The Women’s Movement in the Black Baptist Church, 1880-1920

Darlene Clark Hine, Hine Sight: Black Women and the Re-Construction of American History

Blair L.M. Kelley, Right to Ride: Streetcar Boycotts and African American Citizenship in the Era of Plessy v. Ferguson

Talitha L. LeFlouria, Chained in Silence: Black Women and Convict Labor in the New South

Amrita Chakrabarti Myers, Forging Freedom: Black Women and the Pursuit of Liberty in Antebellum Charleston

Stephanie J. Shaw, What a Woman Ought to Be and Do: Black Professional Women Workers During the Jim Crow Era

LaKisha Michelle Simmons, Crescent City Girls: The Lives of Young Black Women in Segregated New Orleans

Crystal R. Sanders is an assistant professor of history and African American Studies at Pennsylvania State University. She is a native North Carolinian who comes comes from a long line of black women who have made lemonade when served lemons. Sanders's first book, A Chance for Change: Head Start and Mississippi's Black Freedom Struggle (UNC Press 2016) explores how working-class black women who had been denied quality education and well-paying jobs made lemonade out of a federal early childhood education program during the civil rights era.